Lynching

Anthony C. Siracusa

University of Mississippi

Introduction

Following the Civil War, the United States seemed poised for a profound transformation in social relations. African Americans, 179,000 of whom had fought for the union to end slavery, sought and gained full citizenship with the passage of the 14th amendment. The 13th amendment banned involuntary servitude except, problematically, in the case of crime – and ended the system of black bondage that had been a hallmark of US life since the nation’s founding. The 15th amendment brought the promise of enfranchisement for black men. Black families separated during slavery were reunited in cities and towns across the country by the Freedmen’s Bureau in the years following the war, and black men were elected to city councils, state legislatures, and even the US Congress in the period between 1865 and the end of Reconstruction in 1877.

But at every turn, these efforts among black women and men to live as fully self-governing citizens were contested and, by the late 19th century, stymied in the transition from slavery to freedom. The ‘Black Codes’ became an early effort to use the law to restore the social order of slavery as so called ‘vagrancy laws’ were used to punish blacks not employed as sharecroppers by southern planters. And while a Republican congress in Reconstruction attempted to prohibit such legal persecution of blacks by passing the Civil Rights Acts in 1866 and 1875 – the first over a presidential veto from Tennessean Andrew Johnson – the United States Supreme Court in 1883 ultimately invalidated the Civil Rights Act of 1875’s federal protection of black civil rights and paved the way for the legal discrimination and segregation of African Americans in public spaces. These legal efforts to establish non-white Americans as second-class citizens were codified in the infamous 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision, whose majority opinion gave us the language ‘separate but equal’ and made segregation the law of the land for nearly 70 years.

But the law worked in tandem with violence, and in particular extralegal violence in the form of lynching, as many whites sought to restore American social relations to the days of chattel slavery and plantation capitalism.

Between 1877 and 1945, according to the Equal Justice Initiative, more than 4,000 black Americans were killed by whites without a trial – and often in public spaces using spectacle violence.[1] Lynching, as this practice came to be known, was used to prevent black economic advancement, intimidate black men and women into complying with Jim Crow, and suppress political efforts aimed at enfranchising black leaders through electoral processes. Although lynching was not the exclusive method used to achieve these goals, it did emerge as a tragically common practice in the late 19th and early 20th century as ideas about what whiteness was were shifting from a complex tapestry of ethnic-national identities into a singular, cogent, socio-political identity, a phenomenon that emerging colonial powers, including the United States, took note of as they sought to build power over non-white populations across the globe.

The role of lynching in the late 19th and early 20th century also belonged to a discourse around the relationship between civilization and whiteness. Black voting, social equality, and black economic advancement were perceived as a threat to a modern white civilization in the United States – a phenomena most powerfully illustrated by the 1915 film ‘Birth of a Nation.’ On the other hand, the brutality of spectacle lynching was seen by some ‘moderate’ whites as an affront to this modern civilization. These so-called white moderates believed that Jim Crow segregation was a more civilized and humane way of keeping black Americans in their place. Ideas about manhood also punctuated this discourse around civilization and lynching, as white public violence against black men was often justified, falsely as the black journalist Ida B. Wells proved, by accusations that black men raped white women.

In practice, the two seemingly distinct approaches of law and violence were deeply intertwined in maintaining white supremacy: spectacle lynching and public violence functioned to reinforce the strictures of Jim Crow segregation by publicly illustrating the consequences of defiance. The barbarity of lynching between 1877 and 1945 gave way to a nonviolent revolution in the United States, however, in part because the horrors of the holocaust made race-based spectacle lynching increasingly difficult to defend.

Lynching and the Law

In the wake of the Civil War, the four million African Americans held in bondage migrated from rural plantations to cities and towns seeking to give reality to the meaning of freedom by finding lost relatives, building institutions like churches and businesses, and seeking the education denied to them under slavery. Few places were as important to this process as Memphis, Tennessee – located at the top of the Mississippi Delta, America’s fertile crescent and home to some of the largest slaveholding plantations in the country. On April 30, 1866, black soldiers from the Third Colored Infantry, still garrisoned at Fort Pickering in Memphis, scuffled with the white Irish who served on the local police force in Memphis. A congressional inquiry into what followed opened a window into the barbarous white violence that would characterize the next eight decades in the United States. On May 1, 1866, a group of white local people opened fire on a crowd in a South Memphis black neighborhood, leading to three days of fire, bullets, and rape that left 46 African Americans dead, ninety-one houses, four churches, and twelve schools torched, and at least five women were subjected to sexual violence and rape.

The attack in Memphis represented the beginning of a white mob violence mentality directed against black Americans routinely in the late 19th and early 20th century. Whites would formally organize their violent efforts at keeping blacks from exercising political power through the Ku Klux Klan, founded in 1865 by six confederate veterans in Pulaski, Tennessee – including Nathan Bedford Forrest. Based on the ‘night riders’ used to ensure blacks did not leave plantations at night without permission during enslavement, the Klan used spectacle, theatre, and ritual to intimidate and sow fear among black Americans. Congress took action to limit the Klan’s power in 1871, but it’s founding goals of using intimidation and violence to prevent black political and economic advancement was carried forward in cities and towns across the United States between 1871 and the Klan’s later revival in the 1920s.

Two additional legal considerations are essential to understanding how and why lynching and extralegal violence came to be so widespread between 1880 and 1945. First, in 1872, a set of cases related to the rights of slaughterhouse owners to buy and sell meat led individual states to acquire great power in determining the scope and extent of the rights for those people living within their borders. The ‘Slaughterhouse Cases’ narrowed those ‘privileges and immunities’ protected by the federal government – including the guarantee of equal protection for all American citizens provided by the 14th amendment to the U,S. Constitution. The Slaughterhouse Cases were critical in giving states the power to determine and enforce what black Americans could do and could not do.

Secondly, in U.S. v. Cruikshank (1876), the Supreme Court ruled that only those actions perpetrated by the state itself – not the actions of individual citizens – were subject to scrutiny under the equal protection clause of the US constitution. This ruling opened the door for whites intent on preventing black economic and political advancement to use violence and murder with impunity against black Americans.

These cases were concurrent with the efforts of African Americans to exercise their right to vote in the 1870s, a right guaranteed to them by the 15th amendment. But in cities across the United States, black voters were met with violence at the polls. An especially horrific example of how mob violence was used to suppress black voting occurred in Louisiana in 1872. As the African American man P.B.S. Pinchback sought to become the first black governor elected in the United States, black freedmen flocked to the polls to support his candidacy. But on election day they were met at the Colfax County courthouse by whites armed with a canon and rifles. Ultimately as many as 150 black freedmen were killed – the majority of whom surrendered to the armed whites but were killed nonetheless.

When federal troops were withdrawn from the former confederate states in 1877, the final protections on life and property for recently freed Black people were removed. With the repeal of the Civil Rights cases in 1883, black Americans no longer had either legal protection or physical federal protection from wanton white violence. With more than 90% of African Americans living in the former confederacy or border states, legal discrimination against black Americans became widespread – and violence was used routinely to try and prevent black Americans from changing these legal, social, and economic conditions.

Lynching, Civilization, and Empire

As the United States expansion westward accelerated through the 1880s, leading Frederick Jackson Turner to declare that the frontier was officially closed in 1893, the nation described its conquest of the west as a divinely ordained ‘Manifest Destiny.’ Central to this idea of Manifest Destiny was the notion that white Americans developed a unique civilized culture, a culture they were expected to share with non-civilized peoples and in particular those peoples that were indigenous to the Americas. This idea has been captured succinctly by Rudyard Kipling’s phrase ‘The White Man’s Burden.’

The United States had, for decades, fought with native peoples and claimed their land – often using dubious means. But with the passage of the Dawes Act of 1887, this ‘civilizing mission’ gave authority to the President to force native peoples onto reservations as allocated by the US government in exchange for US Citizenship. For those that resisted, as did Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce among many other tribes, they were hunted down and killed.

This language of civilization was also central to the discourse around lynching. As the anti-lynching crusader and journalist Ida B. Wells has written, ‘the Southern white man, as a tribute to the nineteenth-century civilization, was in a manner compelled to give excuses for his barbarism.”[2] These excuses often included the idea that the barbarism of lynching was merely the price of preserving civilization. Whites often used the line that black men raped white women as an excuse to form lynch mobs and kill black men, citing a reasoning that the protection of white womanhood was tantamount to protecting civilization: if we cannot protect our women, all is lost. The idea that women were a class of people to be protected by men was tied to Victorian sensibilities and the ‘cult of true womanhood,’ the idea that women were pretty, pure, pious, and private – not public and therefore needed to be protected publicly by their men. First wave feminists would contest this idea in the late 19th and early 20th century.

But this civilizing discourse found receptive audiences in the colonizing impulses of late 19th century imperial powers, as the emerging nations of Canada and Australia looked to the United States and saw, in their brutality against native peoples and black Americans, that “racial identities” could be central to “the construction of modern political subjectivities.”[3] The United States drew on these racial identities to make claims on what was civilized and who needed civilizing as they fought for and gained military control over the former Spanish colonies of Haiti, Cuba, Guam, and the Philippines. As William Howard Taft, the first American General-Governor of the Philippines, told President William McKinley: “our little brown brothers” required “’fifty or one hundred years” of outside rule “to develop anything resembling Anglo-Saxon political principles and skills.”[4]

At home in the United States, unparalleled immigration in the 1890s led to a complex tapestry of whiteness. Immigrants from England, Ireland, and Scandinavia arrived in large numbers in the middle of the 19th century, while Slovenians, Italians, Poles and others from central and eastern Europe arrived in the late 19th century – creating a hierarchy with western European immigrants at the top in many American cities that translated directly into limited opportunities for central and eastern European immigrants. Chinese immigrants were barred completely with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1888, and the ‘Gentlemen’s Agreement’ of 1907 severely limited Japanese immigration. For African Americans, the largest ‘non-white’ population in the United States, the late 19th and early 20th century became what Rayford Logan has called the ‘nadir’ of African American history – chiefly because lynching and other extra-legal violence continued to be widespread.[5]

Between 1891 and 1901, there were no fewer than 106 documented lynchings per year in the United States. In 1892, the year Ida. B. Wells published ‘Southern Horrors’ documenting lynchings across the South using investigative journalism techniques, the number surged to 230. Between 1901 and 1911, there were on average 85 lynchings per year in the United States. It was not until the mid-1920s that lynching ebbed – and even then there were often dozens of lynchings annually until the eve of the Second World War.[6] Many times, these lynchings were public and intended as spectacle. A ‘carnival like atmosphere’ was often noted, as candy, popcorn, and drinks were often for sale. Public lynchings were often family affairs, and sometimes children were let out of school to attend the public executions.

On May 15, 1916, Jesse Washington – accused of ‘raping’ his white employer’s wife – was pulled from his jail cell by a mob in Robinson, Texas. He was publicly castrated and his fingers were cut from his hands. He was slowly raised and lowered over a bonfire for hours before his blackened body was dismembered and sold piecemeal for souvenirs. More than 10,000 were reported in attendance, including elected officials and law enforcement. While the size of the crowd at the Washington lynching was perhaps exceptionally large, having a crowd to witness lynchings was, itself, not exceptional at all in this period. Postcards of public lynchings, including photographs of individuals with mutilated bodies, were common souvenirs sent to relative who could not attend.

These public and brutal executions of blacks by whites in the United States was accompanied by widespread routine mob violence in the early 20th century. In East St. Louis in July of 1917, as many as 200 black Americans were killed and 6,000 left homeless as whites devastated the black quarter of the city in response to black workers taking positions in wartime industry during the First World War. As soldiers returned home in the summer of 1919, white mobs led violent crusades in dozens of cities – including in Chicago where 23 blacks were killed and nearly 1,000 homes were burned. Such violence became more frequent as whites in northern cities encountered blacks travelling from the rural south as part of the Great Migration, a massive intra-national movement of people that totaled 1.6 million black Americans shifting from the rural south to the urban north between 1916 and 1940. Mob violence continued in the years following the First World War, and in May of 1921 in Tulsa, Oklahoma more than 200 blacks were killed over two days and more than 10,000 people left homeless after 40 blocks were devastated by white mobs.

Black Americans did not sit idly by throughout this process. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was founded in 1909 to battle discrimination and fight the violence used to preserve discrimination. Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) used military symbols and pomp to send a powerful and unified message to white Americans, attracting as many as 800,000 black members and building 700 branches in 38 states by the early 1920s. Self-defense became a common option for blacks, both rural and urban, and Ida B. Wells declared that “a Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home.”[7] After the lynching of Sam Hose in Atlanta in 1899, W.E.B. DuBois, perhaps the most important intellectual of the 20th century and a prominent black leader, proclaimed that if any whites sought to do him harm he would “spray their guts all over the grass.”[8]

Legal efforts to end lynching in the United States, however, were unsuccessful throughout the early 20th century. Despite numerous attempts, no bill designed explicitly to prevent lynching was passed in the United States until December of 2018, when the US Congress finally declared lynching in the United States a hate crime.

Speaking to this common theme of white violence directed at black people for more than 80 years following slavery, the historian and sociologist Charles Payne noted that “the point was there didn’t have to be a point; Black life could be snuffed out on a whim, you could be killed because some ignorant white man didn’t like the color of your shirt or the way you drove a wagon.”[9] Lynching and extralegal violence was used routinely to intimidate and punish blacks who sought political or economic advancement, and whites too frequently killed blacks in a spirit of hate and prejudice – rarely facing legal consequences for doing so before the Second World War.

Lynching and the Paradox of Nonviolent Revolution

While lynchings declined precipitously after the Second World War, perhaps the most famous extra-legal murder of a black American actually took place in August of 1955. Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old black boy from Chicago, was brutally killed by a group of white men in Money, Mississippi. Till was taken from his uncle’s house in the middle of the night, beaten and castrated before a 74 pound cotton gin fan was attached to his neck with barbed wire. He was thrown into the Tallahatchie River in hopes of never being found again. Till was accused by a white woman, Carolyn Bryant, of whistling at her and grabbing her waist.

In 2017, the historian Timothy Tyson revealed that Bryant lied in her testimony about that day, conceding that Till did not in fact touch her. She lamented that “nothing that boy did could ever justify what happened to him.”[10] Sadly, Bryant’s recanting came not only too late, it also exposed the larger lie often used to justify the lynching of black men in the United States. When Till’s body surfaced in the Tallahatchie, his mother – Mamie Elizabeth Till-Mobley – called newspapers all over the country to tell them what those white men in Mississippi had done to her son. She called for an open casket funeral, and drew more than a hundred thousand people to view the brutalized body of her slain son.

The public attention Mamie Elizabeth Till-Mobley brought to the barbaric slaying of her son followed the Nuremberg Trials, which revealed to the world in 1945 and 1946 the extent of Nazi atrocities during the Second World War. It followed the first Universal Declaration of Human Rights outlined by the newly formed United Nations in 1945, and it came at a moment when the United States was claiming a leading role in guaranteeing the rights of dispossessed peoples in the postwar world. In this context, the public horror of lynching was increasingly a problem for a nation seeking to craft a different international image for itself. Such an image was especially important for the United States as it jockeyed for influence in non-white nations across the world, seeking to best the Soviet Union in an emerging Cold War international order by sending a more progressive message about the way it treated non-white peoples at home.

But it was black Americans who led the way in revolutionizing social relations between white and black people in the United States, and they did so by intentionally using nonviolent methods to challenge the brutal violence used for centuries to dehumanize and intimidate black Americans. The sit-in tactic did not originate in 1960, but the tactic did rise to prominence on February 1, 1960 when four students from Greensboro A&T College refused to give up their seats to whites at a segregated lunch counter. By the end of February, more than 30 communities had used the sit-in technique. At year’s end, more than 70,000 women and men – the vast majority of them black – had participated in nonviolent sit-in demonstrations and pickets in an effort to end Jim Crow.[11]

If the power of lynching was derived, in part, from its ability to convey fear, black Americans communicated to the world in the late 1950s and 1960s that they would no longer be intimidated by these violent tactics. Their public witness permanently transformed the trajectory of the nation away from the barbarity of spectacle lynching.

Remembering the history of lynching in the United States, however, is a continual process particularly as activists in 2019 continue to battle against the public killing of unarmed black men and women at the hands of police.

References

“LYNCHING IN AMERICA: CONFRONTING THE LEGACY OF RACIAL TERROR.” Equal

Justice Initiative’s report. Accessed March 5, 2019.

https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/report /.

Lake, Marilyn, and Henry Reynolds. Drawing the Global Colour Line : White Men’s Countries and the Question of Racial Equality. Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Publishing, 2008.

Logan, Rayford W. The Betrayal Of The Negro: From Rutherford B. Hayes To Woodrow Wilson. New York: Da Capo Press, 1997.

“Lynchings: By State and Race,1882-1968.” Accessed March 5, 2019. https://www.famous-trials.com/sheriffshipp/1083-lynchingsstate.

Miller, Stuart Creighton. “Benevolent Assimilation”: The American Conquest of the Philippines, 1899 – 1903. American History. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1982.

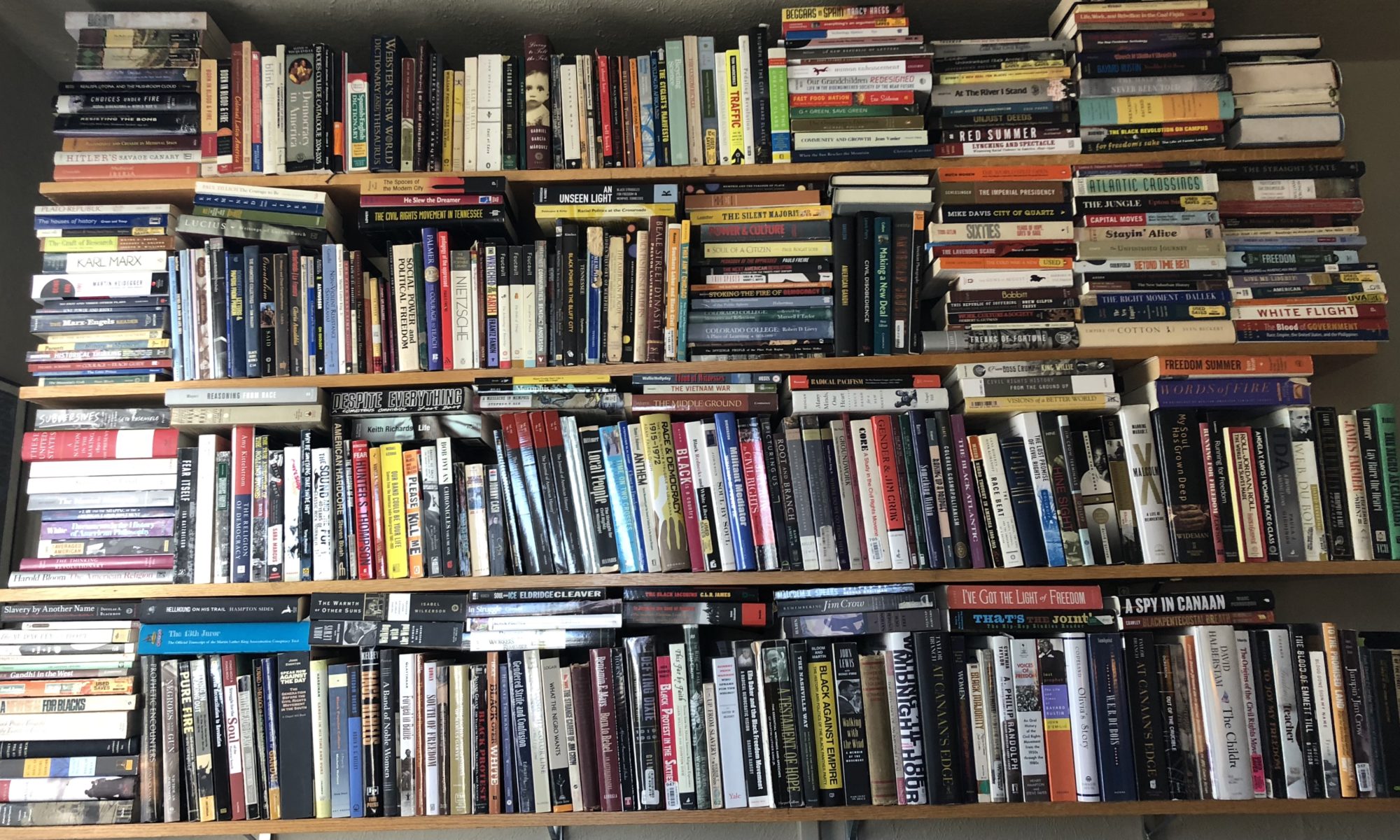

Payne, Charles M. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom : The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995. Contributor biographical information http://www.loc.gov/catdir/bios/ucal051/94024645.html Publisher description http://www.loc.gov/catdir/description/ucal041/94024645.html.

Pease, Donald E., ed. Revisionary Interventions into the Americanist Canon. New Americanists. Durham, N.C: Duke University Press, 1994.

Royster, Jacqueline Jones, ed. Southern Horrors and Other Writings: The Anti-Lynching Campaign of Ida B. Wells, 1892 – 1900. The Bedford Series in History and Culture. Boston: Bedford Books, 1997.

“Sit-in Movement | United States History | Britannica.Com.” Accessed March 5, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/event/sit-in-movement.

Tyson, Timothy B. The Blood of Emmett Till. First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017.

Wells-Barnett, Ida B. The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynchings in the United States, 2015.

[1] “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror,” Equal Justice Initiative’s report, accessed March 5, 2019, https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/report/.

[2] Ida B Wells-Barnett, The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynchings in the United States, 2015.

[3] Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds, Drawing the Global Colour Line : White Men’s Countries and the Question of Racial Equality (Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Publishing, 2008).

[4] Stuart Creighton Miller, “Benevolent Assimilation”: The American Conquest of the Philippines, 1899 – 1903, (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1982), p. 134.

[5] Rayford W. Logan, The Betrayal Of The Negro: From Rutherford B. Hayes To Woodrow Wilson, (New York: Da Capo Press, 1997).

[6] Douglas O. Linder, “Lynchings:By State and Race,1882-1968 *,” accessed March 5, 2019, https://www.famous-trials.com/sheriffshipp/1083-lynchingsstate.

[7] Jacqueline Jones Royster, ed., Southern Horrors and Other Writings: The Anti-Lynching Campaign of Ida B. Wells, 1892 – 1900, The Bedford Series in History and Culture (Boston: Bedford Books, 1997).

[8] Donald E. Pease, ed., Revisionary Interventions into the Americanist Canon, New Americanists (Durham, N.C: Duke University Press, 1994).

[9] Charles M. Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), p. 15.

[10] Timothy B. Tyson, The Blood of Emmett Till, First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017).

[11] “Sit-in Movement | United States History | Britannica.Com,” accessed March 5, 2019, https://www.britannica.com/event/sit-in-movement.